Transcript: Charles Taylor's A Secular Age, Book Brief

15 minute summary of Taylor's A Secular Age, published in 2007

Episode available on Apple and Spotify

Sections:

Introduction (00:00:45)

How we Ended Up in This Secular Age (00:02:25)

The Anthropomorphic Shift (00:06:05)

“God has become unknowable, His voice inaudible against the din of machines and the atonal banshee of the emerging egomania called The Modern… The nature of society itself, urban, industrialized, materialistic, was the background for the godlessness which philosophy and science did not so much discover as ratify” – A.N. Wilson (552)

Ok, we’re starting off with a banger: a fifteen minute summary of a 780 page book. A Secular Age was published in 2007 and was based partly on papers Charles Taylor gave at the Gifford Lecture series, which is a series of talks held in Scotland focused on the study of religion. And oh by the way, this series has been ongoing since the late 1800s.

Charles Taylor was a French-Canadian philosopher and he writes like a philosopher. By that I mean two things. First, he’s mostly trying to be non-partisian. So while he is a Catholic, this is not a work of theology or apologetics.

Secondly, I say he writes like a philosopher because his writing is… awful. As insightful as this book is, and it is an extremely insightful book, I would literally never recommend anyone read it. It’s needlessly long, he repeats himself across sections, and he’ll entertain questions and hypotheticals for pages and then say that there’s no real conclusion to draw from them and moves on. So hopefully, this set of podcasts cover the important points and you can feel like you read a big, long book without having had to actually read the big, long book.

---------- The Main Argument (02:25)

There is one primary question motivating Taylor: In the West broadly construed, how is it that in 1500AD it was virtually unthinkable to not believe in God and in 2000 it is a valid worldview? In other words, how did we get to the secular age we now live in? And, just to go one layer down, we should ask: how is this lack of a belief in god a live option for the masses. There have always been elites and scholars who have been atheists, but what allowed for religion to be displaced from the center of the average person’s life?

So to explore his answer, we’re first going to cover his historical argument at an extremely high level, and then wrap up by detailing a primary condition he develops to support his overall argument. But this is a condition, not a cause. He’s not trying to point his finger at one thing and say: ah, *here* is the cause of our secular age; rather, it’s more about highlighting what he thinks is a condition that allows for the secular age to be possible.

But now on to the features or steps in his historical argument

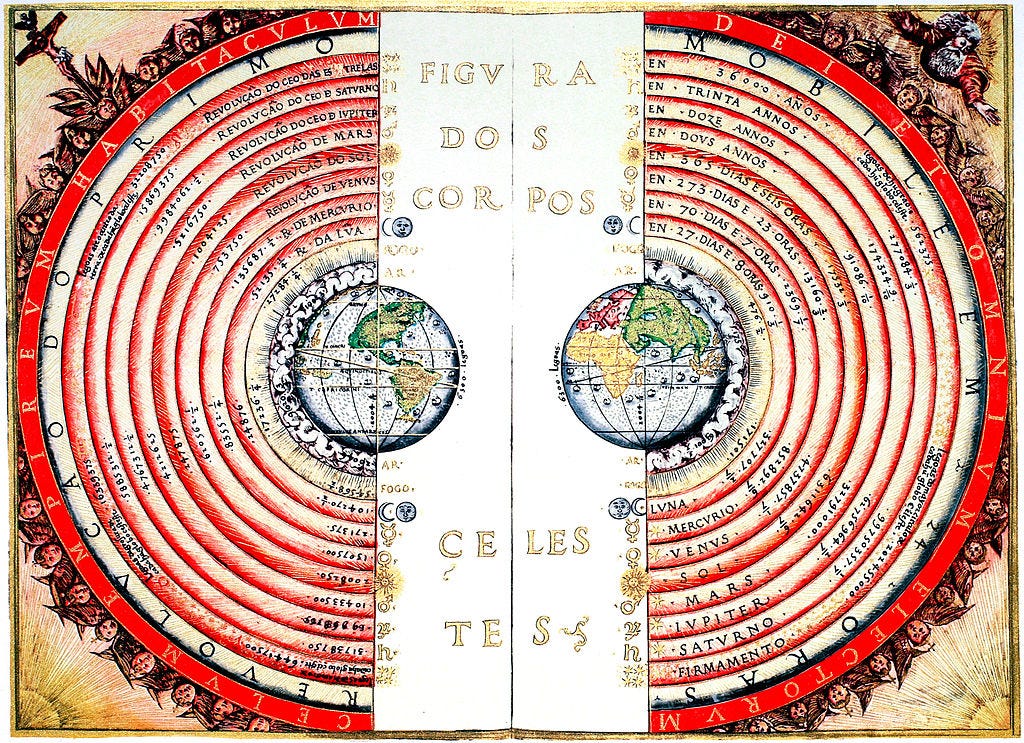

1) In the past, meaning was outside of humans, in an ordered cosmos. Agency was also mostly outside of us (in the form of gods and spirits). Our our job was to just hook into that if we could, but it was never fully within our grasp because the gods and spirits could be spontaneous. We could never fully know the will of God

2) Then we began to see the external world as still ordered, but ordered differently. It looked less random, but also more impersonal. The gods became less spontaneous and the good, became what is good for human flourishing. And we began to have at our disposal what we believed were the tools to understand that order: through human reason, the world was grasp-able, we could understand how things worked and what to do as a result

3) But in situations where we didn’t see the order out there that we expected, it was on us to create that order, to immanentize it, to create the ideal moral world that best allowed humanity to flourish, to create heaven on earth

4) But as meaning and agency continued their inward movement, and the external world became dead matter, that meant we had no blueprint to follow, no god to guide us. The order and meaning of the universe was and is completely on us. We are the gods of the universe, for better or worse.

That’s the basic outline of his argument. So now, with the remaining time we have, we’ll walk through the Anthropomorphic Shift, which get more into the conditions of the steps we just covered.

------- Anthropomorphic Shift (06:05)

To develop our understanding of Taylor’s anthropomorphic shift, we’re going to break it down into two ideas: the disenchanted world, and a related concept, the Buffered Self.

Disenchanted world

In the past, objects and spaces could be sacred, regardless of what we thought of them. In other words, meaning could be external. Saints’ bones could be sacred, for example. The inside of the temple could only be accessed by the head priest at particular times. And at times, they would attach a rope to the priest’s ankle, in case they made a mistake and had to be pulled out of the inner sanctum by others who could not enter. But now, we believe everything is psychological or internal, agency and will and meaning are in individuals, not external.

Related, the cosmos no longer contains signs for us. Astrology, tea leaf reading, reading the cracks of bones, all the same, all relegated to the realm of superstition, *even though* we all kind of keep an interest in it. Baseball players are highly superstitious. Women (mostly) do know what their “sign” is, and will even put it in their profiles on dating apps. In our modern, scientific world view, do we *actually* think that the position of the earth with respect to the stars millions of light years away has an effect on my personality? Well when you put it like that, probably not… but nevertheless, we’re still kind of keeping that around.

So this enchanted world of the past we’ve just described was the context in which people believed in the Christian God. The world was full of spirits, God was just the best one, and he was on your side. Belief was also closely tied to the social. Israel had their god, the Canaanites had their god, etc. Moreover, the more a community believed/worshipped God, the safer the community was or more prosperous. If an individual did not believe, he was a heretic and, importantly, cast out, so he wouldn’t hurt the rest of the society. You can see the self-reinforcing mechanism at play here. Religion, community, individual, all connected and supporting each other.

Buffered Self

Related to the enchanted/disenchanted world, a key concept Taylor develops is that of the buffered self, which he argues is our modern conception of the self. By this he means that over the last few centuries in the West, we have slowly constructed a wall between the self and the outside world. In the past, spirits, that enchanted world we just talked about, were all around us, and sometimes they “affected” us. Positively, a good spirit could guide us, a guardian angel. Negatively, we could get “possessed” by an evil spirit, or demon. This self that can be affected by external agents is the porous self of the past, contrasted with the modern, Buffered Self.

From another angle, as the buffered self is developed and reason is elevated, the person becomes a moral and epistemic agent that looks like an impartial observer. The thinker is now “disintricated” from the universe. Things begin to become subjects of study for us. There is us, and then there is the world out there. There is an objectification of things, which at the same time begins to look like disengagement with the outside world. This perspective, this way of understanding, is what has been called a “view from nowhere”. He calls this a change in our interpretative framework/epistemic predicament. And it is in this condition that you can see how God can now come into question… the being, the existence of god is now a question for us, in a way that it simply wasn’t for our ancestors.

But Taylor makes a point again and again to critique the “Darwin killed god” hypothesis. He argues that we aren’t these hyper-rational agents that simply weigh the facts and then update our worldview. We didn’t say: ah, Mr Darwin here has provided us with new information, so now I will reexamine my entire worldview. Some people did that, but not most. Rather, it was the vibe. Eventually, the conditions changed enough that an argument like Darwin’s could take hold. Such an argument began to resonate with the average person, given our experience of the world as we saw it. As Taylor says, the secularization we have underwent “was not that of a moral outlook bowed to brute facts. Rather we might say that one moral outlook gave way to another. Another model of what was higher triumphed” (563).

But over time, as we start to become more human-centered, we start to think that the good should be good because it is good, not because it’s what god wills. Surely god would only do what is best for us. From that perspective, a wrathful god stops making sense. The God of Abraham and Isaac, the god that told Abraham to kill his son Isaac, stops making sense.

So this is why Taylor argues for both a moral and epistemological change that came with this anthropomorphic shift. As the quote from Wilson at the beginning says, science and reason are just ratifying something else that was already there in the background.

To end this episode, let’s take a second to reflect on our contemporary view of ghosts. How is it that today we can, seemingly, entertain both sides of the debate of whether ghosts exist or not? What is it about our world and ourselves that both options are in some sense live for us? If ghosts do exist, isn’t that kind of a big deal? If they don’t exist, why do we still kind of believe in them? So even bracketing this big idea of believing in god or not, here we see this ambivalence in our modern worldview with respect to similar phenomena. And this is part of what Taylor is getting at. Belief/un-belief in God takes place in a wider context. His criterion for defining our age as a secular one isn’t whether and how many people believe in God; he is focused on the context in which atheism is one option among others, some choice one can make.

So that’s the anthropomorphic shift, the turn inward that Taylor argues helped get us to the present state of things. And that’s all I have for you today. I hope you’ll check out the deep dive episode for Taylor’s A Secular Age where I spend more time on this turn inward, as well as look at other ideas in his book like the flattening of time, the “PC” or political correctness phenomenon that Taylor is describing in the late 90s and early 2000s, that has even more resonance today given the cultural conversation, the loss of meaning, our crisis of identity, and lastly geographic land features as metaphor. And if *none* of that interests you, which I can’t see how that would be possible, my next book brief will be on George Kovacs’ 1990 book The Question of God in Heidegger’s Phenomenology.